Murder in Mind

I didn’t get round to posting my talk on Helen McCloy, which I gave at Bodies from the Library last year. So here it is now. The title is ‘Murder in Mind: The Crime Novels of Helen McCloy.’

I didn’t get round to posting my talk on Helen McCloy, which I gave at Bodies from the Library last year. So here it is now. The title is ‘Murder in Mind: The Crime Novels of Helen McCloy.’

My attention was first drawn to Helen McCloy when her novel, Mr Splitfoot, was listed by H. R. F. Keating as among the 100 best crime novels ever published. It was some years later that I first read one of her novels. And when I did, I was surprised that she wasn’t better known.

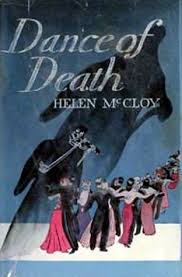

It’s not as if she was one of those writers who produces only a few novels and disappears from view. She had a very long career. She was born in New York City in 1904 – her mother was a writer and her father was managing editor of the New York Evening Sun – and she died in 1994. She wrote around thirty novels, thirteen featuring her series character, Dr Basil Willing, the rest stand-alone thrillers and suspense novels, as well as a number of short stories. Her first novel, Dance of Death, came out in 1938, her last, Burn This, in 1980.

In addition she had a high profile in the world of American crime-writing. In 1950 she was the first female president of the Mystery Writers of America and she got an Edgar in 1954 for her crime fiction reviews. With her husband Davis Dresser, creator of PI Mike Shayne under the pseudonym Brett Halliday, she founded a publishing company and a literary agency. It’s during those years that her outcome as a novelist decreased. And when she did begin to publish more during the 1970s, it was with a string of stand-alone suspense novels, which I find less interesting than her earlier work.

She had only one series character – psychiatrist Basil Willing, who featured in her first novel and in twelve more, most of them written between 1938 and 1956, though two more were to appear at long intervals, Mr Splitfoot in 1968 and Burn This in 1980. Willing also appeared in a number of short stories, notably ‘The Singing Diamonds,’ which appears in The Pleasant Assassin and Other Cases of Basil Willing. The early Basil Willing novels fall in the Golden Age category and employ some Golden Age tropes: notably the box of poisoned chocolates in Who’s Calling? and an impossible crime in the style of John Dickson Carr in Mr Splitfoot.

So why are her novels worth reading?

Her Basil Willing novels have gripping and original plots. McCloy specialised in the intriguing set-up. In her first novel, Dance of Death, published in 1938, the body of young woman is discovered in a deep snow drift in the depths of a New York winter. The body is not just warm but hot, and it turns out that she has died of heat stroke. In The Deadly Truth a woman visits her lover in a lab where he is developing a truth drug. After she’s gone he realises that she has stolen some – with interesting consequences at a cocktail and dinner party later that day. In Cue for Murder, someone playing the part of a corpse turns out really to be dead and must have been murdered by one of three actors in full view of the audience. In the novel that is often regarded as her masterpiece, Through a Glass Darkly, a young woman, Faustina, goes to Willing for help: she has been sacked from her teaching job at a girls’ boarding school because of something uncanny: several witnesses have seen her in two places at the same time. She apparently has a doppelgänger. In Alias Basil Willing, Willing is in a tobacconist’s in Manhattan when another customer follows him into the shop, buys cigarettes, and leaves in a hurry. The man hails a taxi to take him to 51st street with the instruction: ‘Come back and call for me; I am Dr Basil Willing.’ Intrigued, Willing gets into the next taxi and follows him.

It is one thing to have a gripping opening, and it is another thing to follow through and construct an interesting plot and a satisfying resolution. But McCloy did generally succeed in that.

To return to her first novel, Dance of Death, (Martin Edwards describes it as a ‘dazzling debut’ and I agree) McCloy introduces Dr Basil Willing as a psychiatrist attached to the district attorney’s office in New York, concerned mainly with testing the sanity of accused men and the reliability of witnesses. He is an American, but his mother was Russian. He is described as having a ‘thin intelligent face, disturbingly alert eyes and a slightly ironical manner’ – and after studying at Johns Hopkins, he has spent a further eight years in Paris, London and Vienna. He is essentially a Freudian and his claim is that ‘every criminal leaves psychic fingerprints and he can’t wear gloves to hide them’ and that ‘even a small everyday lie is a clue to the personality and preoccupations of the liar.’ One element of the novel might have been ripped from today’s headlines: a fashionable young woman makes money from appearing in adverts for a drug to aid slimming. These days she would be on Instagram and have her own Youtube channel.

Stemming from McCloy’s interest in psychoanalysis was her fascination with duality, with the conscious and the unconscious mind, with the two sides of a person’s nature, with the doppelgänger and the double. I have already mentioned Through a Glass, Darkly. There it appears that a young woman’s doppelgänger commits murder while the young woman herself is miles away and at that very moment is speaking on the phone to her friend and fellow teacher Gisela (Basil’s girlfriend and in later novels his wife and the mother of his daughter). Similarly in Dance of Death Basil recognises the dead woman from a newspaper article, yet it seems that at the very time her body was lying in the snow drift, she was dancing the night away at her own coming out ball.

In one of the Willing novels the murderer is actually suffering from a split personality and doesn’t even know himself that he is the villain. In She Walks Alone, one of McCloy’s standalone thrillers, the narrator comments ‘Now I saw that I had never known [X] If it hadn’t been for Rupert Lord’s money the inner [X] might never have cracked through the apparent [X], a surface enamel fired by social pressure. . . . that apparent [X] was not a deliberate deception, he was another phase of [X’s] nature, just as real as the inner [X]. That was how the apparent [X] had been able to fool me and everyone else. He was part of the truth.’ That is a recurring theme in McCloy’s novels and a chilling one.

McCloy was an intelligent and elegant writer, both witty and ironic. In Through a Glass, Darkly the headmistress of a girl’s school puts forward a case for the existence of psychic phenomenon, including perhaps the doppelgänger.

‘So you believe in it?’ asked Basil.

She replies, ‘I am a modern woman, Dr Willing. That means I believe in nothing.’

So why isn’t McCloy better known? Partly perhaps because there was a gap in her career. She only published three novels in the 1960s, and when she stepped up her output in the 1970s, it was with a series of suspense novels and thrillers, which generally did not have the originality of her earlier books.

Then too, in her early work she was a writer who liked to experiment – in one of the Willing novels, for instance, it is apparently not until very late that he appears. Similarly, The One That Got Away is told by a first person narrator, also a psychiatrist, who observes Willing at work. I admire her boldness, but it led some unevenness in her work.

Neverthess at her best she is a splendid writer. But don’t take my word for it. Her novels and short stories have been reprinted by The Murder Room and are available as ebooks. Try her for yourself.

6 Comments

Margot Kinberg

January 16, 2020I wish I’d been at your talk, Christine – it must have been fascinating! This is really interesting information on a writer that, I think, not enough people have tried. And it’s fascinating to reflect on why some writers are at the forefront of people’s minds, and others get, well, forgotten or nearly so. In this case, I’m glad her work is being reprinted, so that it’s available.

Christine Poulson

January 16, 2020Thanks, Margot! Yes, I was really surprised not to have come across her before, when I’ve read so much Golden Age crime fiction. She has so much going for her.

Martin Edwards

January 16, 2020I enjoyed your original talk and was glad to be reminded of it. She was a talented and interesting writer and I agree she deserves to be remembered. One of the good things to have happened in recent years is that changes in publishing, including the arrival of digital, have meant that it’s easier to make older books widely available and as a result we’ve now got much more choice than ever before. Which has to be a good thing, even if we don’t have more time to read all the great books…

Christine Poulson

January 17, 2020Thanks, Martin! Glad you enjoyed the talk. Yes, it is great that so much is now accessible online, though I do rather regret the days of hunting down books in second-hand bookshops and the thrill of an unexpected discovery.

moira@clothes in books

January 17, 2020Great overview of her work, and I really enjoyed hearing it first. She is so very much open to rediscovery now, I think people will love her. Strong women, great clothes, excellent crime plots – they could be made for me and many others!

Christine Poulson

January 17, 2020Thanks, Moira. I’m sorry really that she didn’t write more Basil Willing novels. He’s a great character. Her writing has a special flavour, I think – and she’s such an intelligent writer.